One of the major criticisms levelled against the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) since its rise to national prominence after Independence is the allegation that the organization is ideologically hostile to Christianity and the teachings of Jesus Christ. To sustain this narrative, critics, often semi-academicians and politically motivated commentators, indulge in their favourite ritual: citing a single book and a single chapter. That book is Bunch of Thoughts, and the chapter is titled “Christian Problem.” This vague invocation is repeatedly weaponized to claim that Guruji Golwalkar, the second Sarsanghchalak of the RSS and widely regarded as one of its principal ideological pillars, vilified Jesus, mocked Christian theology, or denigrated the essence of Christianity. But does this accusation survive even the most basic scrutiny? Is there any textual evidence supporting it? Let us examine the matter factually.

To summarize the long-pending question in one blunt line: there is no textual evidence whatsoever that Guruji Golwalkar criticized Christianity, Christian theology, or Jesus Christ. Guruji did not devote his intellectual energy to theological debates on Christianity. The so-called “evidence” that critics parade is nothing more than a superficial reference to a chapter title, detached from context. In fact, Bunch of Thoughts contains no criticism of the Bible, no theological rejection of Christian doctrine, and no disparaging remarks about Christ. Guruji never analysed or attacked Christian theology. He never questioned Biblical teachings nor commented negatively on essential Christian religious practices. How then did he become the target of this slanderous propaganda? The answer lies in the persistent misinformation machinery of political and missionary lobbies that thrive on distortions.

Bunch of Thoughts is a compilation of Guruji’s public speeches delivered during some of the most turbulent decades in independent India, years marked by Partition trauma, external aggression from Pakistan and China, and internal threats ranging from Maoist insurgency to Islamist radicalism and missionary-backed separatism in the Northeast.

As the present Sarsanghchalak rightly pointed out in a lecture series in 2018, “The Bunch of Thoughts is a collection of speeches which were made in particular context and cannot remain eternally valid.” Guruji’s speeches, addressing a society inflamed with patriotic resolve, were later compiled by Prof. M.A. Venkata Rao. In one chapter, titled ‘Internal Threats’, Guruji discussed three major political challenges India faced. Unfortunately, even seventy-five years after Independence, these very threats, Islamism in the form of Jihad, Communist extremism in the form of Maoism, and missionary-sponsored separatism which turned the Northeast a warzone, remain active confrontations for India’s security forces.

The chapter “Christian Problem” deals exclusively with political activities of certain missionary groups whose operations posed challenges to national sovereignty. Similarly, the chapter on the “Muslim Problem” addresses political and communal issues related to pan-Islamism and the aftermath of Partition. In both cases, Guruji’s critique is directed at political extremism, not at theology, not at scripture, and not at the faith of ordinary Christians or Muslims. The criticism is rooted firmly in national security considerations. This is precisely why India’s defence analysts, under governments of various political hues, including Congress, have repeatedly examined similar issues. Their reports remain publicly available through the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA), founded in 1965 as an autonomous, non-partisan body under the Ministry of Defence. IDSA’s classifications of internal threats mirror Guruji’s framework in Bunch of Thoughts, reinforcing its strategic validity.

It is also important to note that the chapter titles were editorial decisions, not Guruji’s own labels. The content, however, reflects Guruji’s consistent, non-sectarian stance against political extremism masquerading as religious activity. Nowhere in Guruji’s writings or speeches will one find an attack on the core tenets of Christianity or Islam, nor any derogatory reference to the beliefs of common worshippers.

In this context, a comparative evaluation of Guruji’s approach vis-à-vis the views of Mahatma Gandhi becomes essential. Such a comparison exposes a striking truth: while missionary groups often attempt to appropriate Gandhi and Ambedkar and vilify Guruji to suit their anti-Hindutva narrative, it was actually Gandhi and Ambedkar who delivered theological attacks on Christianity. Both questioned the fundamental doctrines of the Church, challenged Christian claims to spiritual exclusivity, and vehemently opposed missionary proselytization. Their criticisms went far deeper, both politically and theologically, than anything Guruji ever said. In fact, Gandhi and Ambedkar’s statements pose far more discomfort to Christian theological doctrine than the political observations Guruji made.

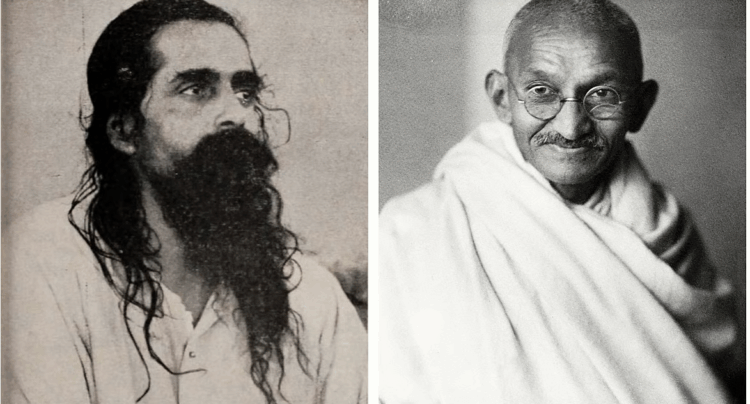

Mahatma Gandhi on Christianity

The most authoritative source for Gandhi’s views on Christianity is his celebrated autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth. In it, he makes a series of candid, even blunt, remarks that question fundamental Christian beliefs, remarks that would be considered blasphemous by orthodox standards and that would certainly offend many common Christian believers.

In his autobiography, Gandhi openly challenges Christianity’s central claim that Jesus is the only incarnate son of God whose death redeems humanity’s sins. He also rejects another core doctrine, that only humans possess souls. Furthermore, Gandhi states clearly that he cannot accept Jesus as “the most perfect man ever born.” He even declares that the sacrificial spirit of Hindus far surpasses that of Christians. Guruji Golwalkar never made any such comparisons, nor did he ever challenge Christian doctrine in this manner.

Gandhi writes:

“It was more than I could believe that Jesus was the only incarnate son of God, and that only he who believed in Him would have everlasting life. If God could have sons, all of us were His sons. If Jesus was like God, or God Himself, then all men were like God and could be God Himself. My reason was not ready to believe literally that Jesus by his death and by his blood redeemed the sins of the world….Philosophically there was nothing extraordinary in Christian principles. From the point of view of sacrifice, it seemed to me that the Hindus greatly surpassed the Christians. It was impossible for me to regard Christianity as a perfect religion or the greatest of all religions.” An Autobiography, pp. 98-99, Edn. 1958

Gandhi further explains his utter lack of interest in the Old Testament:

“I could not possibly read through the Old Testament. I read the book of Genesis, and the chapters that followed invariably sent me to sleep… I disliked reading the book of Numbers.”

While Gandhi admired the Sermon on the Mount, even that admiration came through comparison with the Bhagavad Gita, unlike Savarkar and Vivekananda, who appreciated Biblical teachings without such qualifiers.

In contrast to Gandhi’s lack of connection with the Old Testament, icons of Hindutva like Swami Vivekananda and Veer Savarkar found deep inspiration in the Bible. Savarkar, imprisoned in the Cellular Jail, asked the authorities for two things: milk (denied) and a copy of the Bible (granted). He wrote:

“The life of Jesus Christ and his Sermon on the Mount had always appealed to me… I used to read it daily and to meditate upon the text.”

Savarkar even wrote a poem on the life of Jesus Christ and expressed admiration for the Old Testament, precisely the parts Gandhi disliked. He also cherished Thomas à Kempis’ Imitation of Christ. Swami Vivekananda, too, deeply respected the Sermon on the Mount, especially the teaching: “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.”

Further, in comparing the Bhagavad Gita and the Sermon on the Mount, Gandhiji explains why he cannot embrace Christianity in a more overt manner:

“Not that I do not prize the ideal presented therein; not that some of the precious teachings in the Sermon on the Mount have not left a deep impression upon me, but I must confess… that when doubt haunts me, when disappointments stare me in the face, and when I see not one ray of light on the horizon, I turn to the Bhagavadgita, and find a verse to comfort me; and I immediately begin to smile in the midst of overwhelming sorrow. My life has been full of external tragedies, and if they have not left any visible and indelible effect on me, I owe it to the teachings of the Bhagavadgita.” — Young India, 6-8-1925

Gandhi also condemned Western Christianity as a distortion of Christ’s message:

“I consider Western Christianity in its practical working a negation of Christ’s Christianity…” – Young India, 22-9-1921

And even: “Today I rebel against orthodox Christianity, as I am convinced that it has distorted the message of Jesus…”— Harijan, 30-5-1936.

Gandhi even questioned the historicity of Jesus as a living, personal presence. When a Christian missionary asked him, ‘do you definitely feel the presence of the living Christ within you’, he answered: “If it is the historical Jesus surnamed Christ that you refer to, I must say I do not. If it is an adjective signifying one of the names of God, then I must say I do feel, the presence of God—call Him Christ, call Him Krishna, call Him Rama. We have one thousand names to denote God, and if I did not feel the presence of God within me, I see so much of misery and disappointment every day that I would be a raving maniac and my destination would be the Hooghli.” Young India, 6-8-1925.

He also questioned the authenticity of the Gospels and rejected them as grafts on Christ’s teachings.: “I do not accept everything in the Gospels as historical truth. And it must be remembered that he was working amongst his own people, and he said he had not come to destroy but to fulfil. I draw a great distinction between the Sermon on the Mount and the Letters of Paul. They are a graft on Christ’s teaching, his own gloss apart from Christ’s own experience.”— Young India, 19-1-1928

In terms of theological criticism directed at Christianity, Gandhiji engaged deeply, whereas Guruji did not offer even a minor critique of Christian beliefs. Instead, Guruji maintained a stance of spiritual silence regarding the religious aspects of Christianity, consistently upholding the eternal Hindu ethos of universal harmony and acceptance in relation to it.

Gandhiji or Guruji?

On the issue of conversion, Gandhi’s views align very closely with Guruji’s stance in Bunch of Thoughts. In Young India, Gandhi calls proselytization “unhealthy”, criticizes missionary medical and educational coercion, and denounces conversion as a financial enterprise:

“I hold that proselytizing under the cloak of humanitarian work is, to say the least, unhealthy… Conversion nowadays has become a matter of business…” (Young India, 23-4-1931)

As Guruji was firm in his stance against the forced conversion of tribals and villagers, Gandhiji likewise opposed the missionaries’ ‘ulterior motive of converting India to Christianity.’ In an article published in Harijan. (Harijan, 28-9-1935)

Gandhiji even advised missionaries to abandon the goal of converting the world: “Cease to think that you want to convert the whole world to your interpretation of Christianity…” (Harijan, 23-3-1940)

Guruji Golwalkar’s observations in Bunch of Thoughts similarly expose the political motives behind certain missionary networks. He relies on documented evidence, including news reports, statements from Church leadership, and the Niyogi Committee Report. In the Buch of Thoughts, at one point he laments: “Jesus had called upon his followers to give their all to the poor… But what have his followers done in practice? Wherever they have gone, they have proved to be not ‘bloodgivers’ but ‘bloodsuckers’? What is the fate of all those lands colonised by these so-called disciples of Christ?,”

It was Gandhiji, not Guruji Golwalkar, issued the strongest theological critiques of Christianity. Gandhi questioned the divinity of Christ, the exclusivity of salvation, the authenticity of the Gospels, the morality of proselytization, and the legitimacy of Western Christianity itself. To our dismay, Gandhiji even refused to send his children to a school in South Africa only because it was run by Christians! (Autobiography, Part 3, Chapter 5).

Guruji, in contrast, never critiqued Christian theology or Biblical doctrine. His observations were restricted solely to political threats posed by certain missionary groups. His criticism were grounded in national security concerns, a stance even many modern Christian believers have confirmed. As we see today, the contemporary Christian believer who may not appreciate Gandhi’s theological rejection of Christianity will find Guruji’s position far more acceptable, as it is directed not at faith, but at politically motivated extremism.

(The writer is a journalist, fellow at the Centre for South Indian Studies)

Discussion about this post