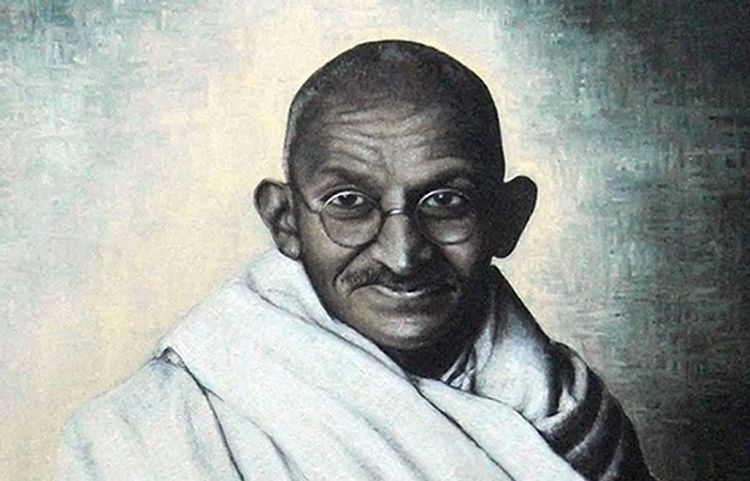

Though the Hindu Mahasabha was established by the renowned scholars and national leaders like Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, it has gained notoriety as being associated with Nathuram Vinayak Godse in our times. Following the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, the Hindu Mahasabha has gradually faded into oblivion in post-independence India. Yet, history reminds us that during its prime, the Mahasabha was a formidable organization that contributed significantly to India’s freedom struggle, producing numerous strong leaders. Among these were luminaries like Swami Shraddhanand, Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, Lala Lajpat Rai, Bhai Paramanand, B.S. Munje, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, and Syama Prasad Mookerjee. Most remarkably, one of the most famous figures associated with its early years was none other than Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, later revered as Mahatma Gandhi!

Historical accounts indicate that Gandhi chose the inaugural session of the Hindu Mahasabha as the platform for his initial political engagement in India. After his eventful years in South Africa, Gandhi returned to India in January 1915. Following a series of modest public events in his native region, he traveled to Calcutta in March. His journey included a visit to Santiniketan, after which he headed to Haridwar to participate in the Kumbh Mela. On March 29, 1915, Gandhi recorded in his diary: “Address by Hindu Sabha. Meeting with Mr. Holland. Party at Mr. Das’s.” (Diary for 1915, The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol. 13, Page 163).

In early April, Gandhi arrived in Haridwar. His key engagements there included attending the Hindu Mahasabha conference and meeting Mahatma Munshiram, a prominent leader of the Arya Samaj and the Hindu Sabha at the time. Later, Munshiram became widely known as Swami Shraddhanand, a staunch reformer and martyr who fell victim to Jihadi violence. Even during his time in South Africa, Gandhi respectfully addressed Munshiram as “Mahatma,” and his letters, filled with reverence, is included in Gandhi’s collected works.

Until 1915, the Hindu Mahasabha was not a national organisation. The regional Hindu Sabhash were confined to certain provinces, with the Punjab Hindu Sabha being the most prominent. Decisions taken at the fifth Punjab Hindu Conference in Ambala and the sixth session in Ferozepur culminated in the calling of a national platform, the Sarvadeshak Hindu Mahasabha meeting at Haridwar, coinciding with the Kumbh Mela. This landmark session saw Gandhi, along with Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya and Swami Shraddhanand (then Mahatma Munshiram), participating as a founding leader. Gandhi not only attended but also extended his ‘strong’ support to the organization through his speech.

Notably, it was during this period, 1915-16, Gandhiji cultivated contacts with then prominent public figures like, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Mrs. Annie Besant, Lala Lajpatrai, Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya and members of the Servants of India Society in Poona, Acharya Vinoba Bhave, Mashruwala, Mahadev Desai, Rajendra Prasad, Kripalani, Kalelkar, Jamnalal Bajaj, C. F. Andrews and others. The Kumbh Mela and the Hindu Mahasabha Conference in 1915 served as the stage for Gandhi’s initial efforts to garner public support in northern India after his return from Africa. In fact, the Hindu Mahasabha Conference symbolically marked his political debut in the Hindi heartland.

In his autobiography, Gandhi reflected extensively on his Haridwar visit, noting that he first realized the far-reaching impact of his South African endeavors on the Indian populace during the Kumbh Mela. Pilgrims flocked to his tent for a glimpse of him, leaving him astonished. In his own words, Gandhi described the experience in ‘The Story of My Experiments with Truth’: “My business was mostly to keep sitting in the tent giving darshan and holding religious and other discussions with numerous pilgrims who called on me. This left me not a minute which I could call my own. I was followed even to the bathing ghat by these darshan-seekers, nor did they leave me alone whilst I was having my meals. Thus it was in Hardvar that I realized what a deep impression my humble services in South Africa had made throughout the whole of India.”

The first session of the Sarvadeshak Hindu Mahasabha, held parallel to these events, emphasized national Hindu unity and social reform as its primary agenda. Although no direct evidence exists to confirm that Gandhi attended the session upon the invitation of Mahatma Munshiram, letters exchanged between the two via telegram before the session suggest some level of coordination.

Magha Krishna Paksha 8 [February 8, 1915]

MAHATMAJI,

I had your wire; my reply telegram must have reached you. I had written to Mr. Andrews asking him to thank you for the trouble you took looking after my children and for the affection you showered on them. But, as I am anxious to pay my humble respects to you, I deem it my duty to go there without waiting for an invitation. I hope to wait on you on my way back from Bolpur.

Yours respectfully,

MOHANDAS GANDHI

Gandhiji sent this letter to Munshiramji in February. In it, he mentions a telegram sent by Munshiramji and his response to it. The content of these communications is not available in Gandhiji’s Collected Works. However, based on the available records, Gandhiji arrived in Kangri (Haridwar) on April 6, 1915.

Swami Shraddhanand’s biographer gives an outline about their friendship and this historical visit: “His friendship with C.F. Andrews brought Munshiram into contact with Rabindranath Tagore, and especially with Mahatma Gandhi. When in 1913-14 Gandhi asked Gokhale to collect some money to support his South African satyagraha, the Gurukul had responded admirably: by foregoing some extra food and doing manual work the students collected 1500 rupees for the fund. Gandhi wrote a personal letter of thanks to Munshiram, telling him how C.F. Andrews’ description of the Gurukul and its principal made him want to visit him soon. When the pupils of the Phoenix Ashram came to India, they spent several months at the Gurukul, and in April 1915 Mahatma Gandhi himself arrived on his first visit.”

In his diary entry for Thursday, April 8, 1915, Gandhiji records four key activities: “Visit to Jwalapur Mahavidyalaya. Visit to Hindu Sabha and Rishikul. Address from Gurukul students. Raojibhai arrived, also Kotwal.” (Diary for 1915, The Collected Work of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol. 13, PageNo.164).

Of the above, the details of Gandhiji’s speech to the students of the Gurukul are included in his Collected Works. The speech is as follows:

SPEECH AT GURUKUL, HARDWAR

April 8, 1915

An address of welcome was presented to Mr. Gandhi by the Brahmacharis of Gurukul Kangri on 8th April when Mr. and Mrs. Gandhi visited Hardwar in connection with the Kumbhi. Professor Mahish Charan Sinha with his band of Brahmacharis went to receive him. Brahmachari Budhaduri read the address. . . .

Mr. Gandhi replied:

I feel indebted to Mahatmaji for his love. I came to Hardwar only to pay my respects to Mahatma Munshiram, as Mr. Andrews has pointed out his name as one of the three great men whom I ought to see in India.

He thanked the Brahmacharis for the help they sent to their Indian brothers in Africa and felt specially grateful to the Brahmacharis and the Mahatma for the love and affection they extended towards his Phoenix boys while visiting Gurukul and felt that his pilgrimage to Gurukul was satisfactory. He said:

I am proud that Mahatmaji has called me his brother in a letter. Please pray that I may deserve his fraternity. I have come after 28 years to my country. I can give no advice. I have come to seek guidance and am ready to bow down to anyone who is devoted to the service of the Motherland and I am ready to lay down my life in the service of my country and I shall no more go abroad. One of my brothers is gone.2 I want guidance. I hope the Mahatmaji will take his place and be a brother to me now.

To the Brahmacharis, he said:

Whatever your aim is, is the aim of all of us. May God fulfil our mission.

Mahatma Munshiram, while welcoming him, said that he was glad to hear that he would live in India and would not go abroad like others to serve India from outside. He hoped that Mr. Gandhi would be the beacon light of India.

The Hindu, 12-4-1915

1 The Bengalee, 1-4-1915, has “would”.

2 Laxmidas Gandhi

(Source: The Complete Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol. 13; Page: 46)

More evidence

In the Cambridge University journal Modern Asian Studies (Volume 9, Number 2), Richard Gordon (Oxford University) published an article in 1975 titled ‘The Hindu Mahasabha and the Indian National Congress, 1915-1926’. This article provides detailed information about Mahatma Gandhi’s participation in the Hindu Mahasabha conference. Gordon not only confirms Gandhi’s attendance but also highlights how he strongly supported the Hindu Mahasabha through his speech at the event. It’s worth noting that Gandhiji subsequently adopted many of the objectives and agendas previously championed by the Hindu Mahasabha.

“Gandhi had been fostering support in north India since his return to India. In 1915, he spoke at Hardwar in support of the All-India Hindu Mahasabha. In December 1916, he presided at the First All-India One Language and One Script Conference at Lucknow. In April I9I9 he became president of a subcommittee of the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, to popularise Hindi in the Bombay and Madras Presidencies. He was particularly successful among the Marwari communities in north India. The Marwari Agarwala Conference in I9 I 9 donated Rs. 50.0001- for the spread of Hindi.” (Page: 161)

Gandhiji’s speech reportedly impressed the other leaders of the Hindu Mahasabha, as mentioned in a biography of Swami Shraddhanand (Mahatma Munshiram) authored by J.T.F. Jordens, titled Swami Shraddhanand: His Life and Causes.

A concise account of this historic event is also provided by researcher Prabhu Narayan Bapu in his thesis, Constructing Nation and History: Hindu Mahasabha in Colonial North India 1915-1930 (School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London):

“In the 1920s and 1930s, Gandhi had an evolving relationship with Hindu Mahasabha leaders and managed to rally a significant number of them behind him. He attended the inaugural meeting of the All-India Hindu Sabha in Hardwar in April 1915 and spoke strongly in support of it.36 His passionate speech made an impact on Swami Shraddhananda, who had collected funds for Gandhi’s work while the latter was in South Africa.”

In 1919, during the Non-Cooperation Movement and the Anti-Rowlatt Satyagraha, Mahatma Gandhi received significant support from Swami Shraddhanand, who was also a leader of the Hindu Mahasabha. Gandhi maintained not only a personal but also an organizational relationship with other Hindu Mahasabha leaders like Lala Lajpat Rai and Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya. He strongly opposed the communal narrative labeling Lala Lajpat Rai and Malaviya as anti-Islamic, firmly countering such divisive propaganda. Historical records show instances of Gandhi and Swami Shraddhanand working together, including during the Vaikom Satyagraha and in various Congress meetings where Swamiji, a former national president of the Congress, played an active role. However, the dynamics between Gandhi and the Hindu Mahasabha began to shift with the rise of leaders like Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and B.S. Munje within the Mahasabha.

Revisiting this century-old history raises pertinent questions about the vast corpus of so-called “impartial” biographies of Gandhi written and published over the decades. When examined in the light of these “new discoveries”, the portrayal of Gandhi’s history challenges the credibility of these works. This selective omission of historical truths highlights a deliberate attempt to obscure the collaborative relationship between Gandhi and the early Hindu Mahasabha.

Ironically, while researchers funded by the government have spent years scrutinizing an alleged but nonexistent connection between the RSS and the Hindu Mahasabha, the finger-pointing against RSS and other nationalist freedom leaders for their alleged “association” with Gandhi’s assassination rests merely on tenuous personal links to Hindu Mahasabha leaders decades prior. When history identifies Gandhi himself as one of the founding leaders of the Hindu Mahasabha, the longstanding left-Islamist propaganda that has deeply polarized the political landscape begins to unravel.

References:

1. The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Volume 12

2. The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Volume 13

3. The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Volume 14

4. Richard Gordon (Oxford University) ‘The Hindu Mahasabha and the Indian National Congress, 1915-1926. Modern Asian Studies (Volume 9, Number 2, 1975)

5. Prabhu Narayan Bapu, Constructing Nation and History: Hindu Mahasabha in Colonial North India 1915-1930 (School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London)

6. A Review of the History and Work of the Hindu Mahasabha and The Hindu Sanghatan Movement by Indra Prakash

7. J.T.F. Jordens, Swami Shraddhanand: His Life and Causes

Discussion about this post